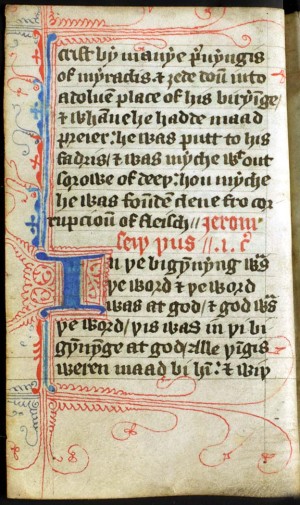

Middle English (c. 1100 – c. 1500)

Great Vowel Shift

A major factor separating Middle English from Modern English is known as the Great Vowel Shift, a radical change in pronunciation during the 15th, 16th and 17th Century, as a result of which long vowel sounds began to be made higher and further forward in the mouth (short vowel sounds were largely unchanged). In fact, the shift probably started very gradually some centuries before 1400, and continued long after 1700 (some subtle changes arguably continue even to this day). Many languages have undergone vowel shifts, but the major changes of the English vowel shift occurred within the relatively short space of a century or two, quite a sudden and dramatic shift in linguistic terms. It was largely during this short period of time that English lost the purer vowel sounds of most European languages, as well as the phonetic pairing between long and short vowel sounds.

The causes of the shift are still highly debated, although an important factor may have been the very fact of the large intake of loanwords from the Romance languages of Europe during this time, which required a different kind of pronunciation. It was, however, a peculiarly English phenomenon, and contemporary and neighbouring languages like French, German and Spanish were entirely unaffected. It affected words of both native ancestry as well as borrowings from French and Latin.

In Middle English (for instance in the time of Chaucer), the long vowels were generally pronounced very much like the Latin-derived Romance languages of Europe (e.g. sheep would have been pronounced more like “shape”; me as “may”; mine as “meen”; shire as “sheer”; mate as “maat”; out as “oot”; house as “hoose”; flour as “floor”; boot as “boat”; mode as “mood”; etc). William the Conqueror’s “Domesday Book”, for example, would have been pronounced “doomsday”, as indeed it is often erroneously spelled today. After the Great Vowel Shift, the pronunciations of these and similar words would have been much more like they are spoken today. The Shift comprises a series of connected changes, with changes in one vowel pushing another to change in order to “keep its distance”, although there is some dispute as to the order of these movements. The changes also proceeded at different times and speeds in different parts of the country.

Thus, Chaucer’s word lyf (pronounced “leef”) became the modern word life, and the word five (originally pronounced “feef”) gradually acquired its modern pronunciation. Some of the changes occurred in stages: although lyf was spelled life by the time of Shakespeare in the late 16th Century, it would have been pronounced more like “lafe” at that time, and only later did it acquired its modern pronunciation. It should be noted, though, that the tendency of upper-classes of southern England to pronounce a broad “a” in words like dance, bath and castle (to sound like “dahnce”, “bahth” and “cahstle”) was merely an 18th Century fashionable affectation which happened to stick, and nothing to do with a general shifting in vowel pronunciation.

The Great Vowel Shift gave rise to many of the oddities of English pronunciation, and now obscures the relationships between many English words and their foreign counterparts. The spellings of some words changed to reflect the change in pronunciation (e.g. stone from stan, rope from rap, dark from derk, barn from bern, heart from herte, etc), but most did not. In some cases, two separate forms with different meaning continued (e.g. parson, which is the old pronunciation of person). The effects of the vowel shift generally occurred earlier, and were more pronounced, in the south, and some northern words like uncouth and dour still retain their pre-vowel shift pronunciation (“uncooth” and “door” rather than “uncowth” and “dowr”). Busy has kept its old West Midlands spelling, but an East Midlands/London pronunciation; bury has a West Midlands spelling but a Kentish pronunciation. It is also due to irregularities and regional variations in the vowel shift that we have ended up with inconsistencies in pronunciation such as food (as compared to good, stood, blood, etc) and roof (which still has variable pronunciation), and the different pronunciations of the “o” in shove, move, hove, etc.

Great Vowel Shift pronunciation changes (35 sec) (from National Science Foundation).

Other changes in spelling and pronunciation also occurred during this period. The Old English consonant X – technically a “voiceless velar fricative”, pronounced as in the “ch” of loch or Bach – disappeared from English, and the Old English word burX (place), for example, was replaced with “-burgh”, “-borough”, “-brough” or “-bury” in many place names. In some cases, voiceless fricatives began to be pronounced like an “f” (e.g. laugh, cough). Many other consonants ceased to be pronounced at all (e.g. the final “b” in words like dumb and comb; the “l” between some vowels and consonants such as half, walk, talk and folk; the initial “k” or “g” in words like knee, knight, gnaw and gnat; etc). As late as the 18th Century, the “r” after a vowel gradually lost its force, although the “r” before a vowel remained unchanged (e.g. render, terror, etc), unlike in American usage where the “r” is fully pronounced.

So, while modern English speakers can read Chaucer’s Middle English (with some difficulty admittedly), Chaucer’s pronunciation would have been almost completely unintelligible to the modern ear. The English of William Shakespeare and his contemporaries in the late 16th and early 17th Century, on the other hand, would be accented, but quite understandable, and it has much more in common with our language today than it does with the language of Chaucer. Even in Shakespeare’s time, though, and probably for quite some time afterwards, short vowels were almost interchangeable (e.g. not was often pronounced, and even written, as nat, when as whan, etc), and the pronunciation of words like boiled as “byled”, join as “jine”, poison as “pison”, merchant as “marchant”, certain as “sartin”, person as “parson”, heard as “hard”, speak as “spake”, work as “wark”, etc, continued well into the 19th Century. We retain even today the old pronunciations of a few words like derby and clerk (as “darby” and “clark”), and place names like Berkeley and Berkshire (as “Barkley” and “Barkshire”), except in America where more phonetic pronunciations were adopted.

The English Renaissance

The next wave of innovation in English vocabulary came with the revival of classical scholarship known as the Renaissance. The English Renaissance roughly covers the 16th and early 17th Century (the European Renaissance had begun in Italy as early as the 14th Century), and is often referred to as the “Elizabethan Era” or the “Age of Shakespeare” after the most important monarch and most famous writer of the period. The additions to English vocabulary during this period were deliberate borrowings, and not the result of any invasion or influx of new nationalities or any top-down decrees.

Latin (and to a lesser extent Greek and French) was still very much considered the language of education and scholarship at this time, and the great enthusiasm for the classical languages during the English Renaissance brought thousands of new words into the language, peaking around 1600. A huge number of classical works were being translated into English during the 16th Century, and many new terms were introduced where a satisfactory English equivalent did not exist.

Words from Latin or Greek (often via Latin) were imported wholesale during this period, either intact (e.g. genius, species, militia, radius, specimen, criterion, squalor, apparatus, focus, tedium, lens, antenna, paralysis, nausea, etc) or, more commonly, slightly altered (e.g. horrid, pathetic, iilicit, pungent, frugal, anonymous, dislocate, explain, excavate, meditate, adapt, enthusiasm, absurdity, area, complex, concept, invention, technique, temperature, capsule, premium, system, expensive, notorious, gradual, habitual, insane, ultimate, agile, fictitious, physician, anatomy, skeleton, orbit, atmosphere, catastrophe, parasite, manuscript, lexicon, comedy, tragedy, anthology, fact, biography, mythology, sarcasm, paradox, chaos, crisis, climax, etc). A whole category of words ending with the Greek-based suffixes “-ize” and “-ism” were also introduced around this time.

Sometimes, Latin-based adjectives were introduced to plug “lexical gaps” where no adjective was available for an existing Germanic noun (e.g. marine for sea, pedestrian for walk), or where an existing adjective had acquired unfortunate connotations (e.g. equine or equestrian for horsey, aquatic for watery), or merely as an additional synonym (e.g. masculine and feminine in addition to manly and womanly, paternal in addition to fatherly, etc). Several rather ostentatious French phrases also became naturalized in English at this juncture, including soi-disant, vis-à-vis, sang-froid, etc, as well as more mundane French borrowings such as crêpe, étiquette, etc.

Some scholars adopted Latin terms so excessively and awkwardly at this time that the derogatory term “inkhorn” was coined to describe pedantic writers who borrowed the classics to create obscure and opulent terms, many of which have not survived. Examples of inkhorn terms include revoluting, ingent, devulgate, attemptate, obtestate, fatigate, deruncinate, subsecive, nidulate, abstergify, arreption, suppeditate, eximious, illecebrous, cohibit, dispraise and other such inventions. Sydney Smith was one writer of the period with a particular penchant for such inkhorn terms, including gems like frugiverous, mastigophorus, plumigerous, suspirous, anserous and fugacious, The so-called Inkhorn Controversy was the first of several such ongoing arguments over language use which began to erupt in the salons of England (and, later, America). Among those strongly in favour of the use of such “foreign” terms in English were Thomas Elyot and George Pettie; just as strongly opposed were Thomas Wilson and John Cheke.

However, it is interesting to note that some words initially branded as inkhorn terms have stayed in the language and now remain in common use (e.g. dismiss, disagree, celebrate, encyclopaedia, commit, industrial, affability, dexterity, superiority, external, exaggerate, extol, necessitate, expectation, mundane, capacity and ingenious). An indication of the arbitrariness of this process is that impede survived while its opposite, expede, did not; commit and transmit were allowed to continue, while demit was not; and disabuse and disagree survived, while disaccustom and disacquaint, which were coined around the same time, did not. It is also sobering to realize that some of the greatest writers in the language have suffered from the same vagaries of fashion and fate. Not all of Shakespeare’s many creations have stood the test of time, including barky, brisky, conflux, exsufflicate, ungenitured, unhair, questrist, cadent, perisive, abruption, appertainments, implausive, vastidity and tortive. Likewise, Ben Jonson’s ventositous and obstufact died a premature death, and John Milton’s impressive inquisiturient has likewise not lasted.

There was even a self-conscious reaction to this perceived foreign incursion into the English language, and some writers tried to deliberately resurrect older English words (e.g. gleeman for musician, sicker for certainly, inwit for conscience, yblent for confused, etc), or to create wholly new words from Germanic roots (e.g. endsay for conclusion, yeartide for anniversary, foresayer for prophet, forewitr for prudence, loreless for ignorant, gainrising for resurrection, starlore for astronomy, fleshstrings for muscles, grosswitted for stupid, speechcraft for grammar, birdlore for ornithology, etc). Most of these were also short-lived. John Cheke even made a valiant attempt to translate the entire “New Testament” using only native English words.

The 17th Century penchant for classical language also influenced the spelling of words like debt and doubt, which had a silent “b” added at this time out of deference to their Latin roots (debitum and dubitare respectively). For the same reason, island gained its silent “s”, scissors its “c”, anchor, school and herb their “h”, people its “o” and victuals gained both a “c” and a “u”. In the same way, Middle English perfet and verdit became perfect and verdict (the added “c” at least being pronounced in these cases), faute and assaut became fault and assault, and aventure became adventure. However, this perhaps laudable attempt to bring logic and reason into the apparent chaos of the language has actually had the effect of just adding to the chaos. Its cause was not helped by examples such the “p” which was added to the start of ptarmigan with no etymological justification whatsoever other than the fact that the Greek word for feather, ptera, started with a “p”.

Whichever side of the debate one favours, however, it is fair to say that, by the end of the 16th Century, English had finally become widely accepted as a language of learning, equal if not superior to the classical languages. Vernacular language, once scorned as suitable for popular literature and little else – and still criticized throughout much of Europe as crude, limited and immature – had become recognized for its inherent qualities.

Printing Press and Standardization

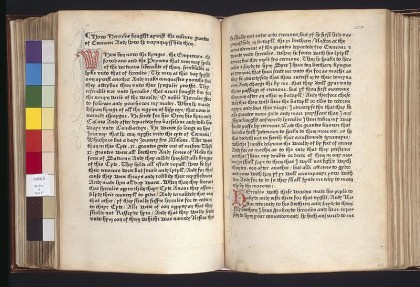

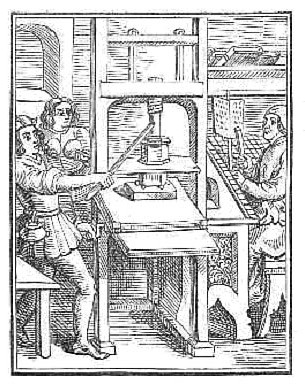

The final major factor in the development of Modern English was the advent of the printing press, one of the world’s great technological innovations, introduced into England by William Caxton in 1476 (Johann Gutenberg had originally invented the printing press in Germany around 1450). The first book printed in the English language was Caxton’s own translation, “The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye”, actually printed in Bruges in 1473 or early 1474. Up to 20,000 books were printed in the following 150 years, ranging from mythic tales and popular stories to poems, phrasebooks, devotional pieces and grammars, and Caxton himself became quite rich from his printing business (among his best sellers were Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” and Thomas Malory’s “Tales of King Arthur”). As mass-produced books became cheaper and more commonly available, literacy mushroomed, and soon works in English became even more popular than books in Latin.

At the time of the introduction of printing, there were five major dialect divisions within England – Northern, West Midlands, East Midlands (a region which extended down to include London), Southern and Kentish – and even within these demarcations, there was a huge variety of different spellings. For example, the word church could be spelled in 30 different ways, people in 22, receive in 45, she in 60 and though in an almost unbelievable 500 variations. The “-ing” participle (e.g. running) was said as “-and” in the north, “-end” in the East Midlands, and “-ind” in the West Midlands (e.g. runnand, runnend, runnind). The “-eth” and “-th” verb endings used in the south of the country (e.g. goeth) appear as “-es” and “-s” in the Northern and most of the north Midland area (e.g. goes), a version which was ultimately to become the standard.

The Chancery of Westminster made some efforts from the 1430s onwards to set standard spellings for official documents, specifying I instead of ich and various other common variants of the first person pronoun, land instead of lond, and modern spellings of such, right, not, but, these, any, many, can, cannot, but, shall, should, could, ought, thorough, etc, all of which previously appeared in many variants. Chancery Standard contributed significantly to the development of a Standard English, and the political, commercial and cultural dominance of the “East Midlands triangle” (London-Oxford-Cambridge) was well established long before the 15th Century, but it was the printing press that was really responsible for carrying through the standardization process. With the advent of mass printing, the dialect and spelling of the East Midlands (and, more specifically, that of the national capital, London, where most publishing houses were located) became the de facto standard and, over time, spelling and grammar gradually became more and more fixed.

Some of the decisions made by the early publishers had long-lasting repercussions for the language. One such example is the use of the northern English they, their and them in preference to the London equivalents hi, hir and hem (which were more easily confused with singular pronouns like he, her and him). Caxton himself complained about the difficulties of finding forms which would be understood throughout the country, a difficult task even for simple little words like eggs. But his own work was far from consistent (e.g. booke and boke, axed and axyd) and his use of double letters and the final “e” was haphazard at best (e.g. had/hadd/hadde, dog/dogg/dogge, well/wel, which/whiche, fellow/felow/felowe/fallow/fallowe, etc). Many of his successors were just as inconsistent, particularly as many of them were Europeans and not native English speakers. Sometimes different spellings were used for purely practical reasons, such as adding or omitting letters merely to help the layout or justification of printed lines.

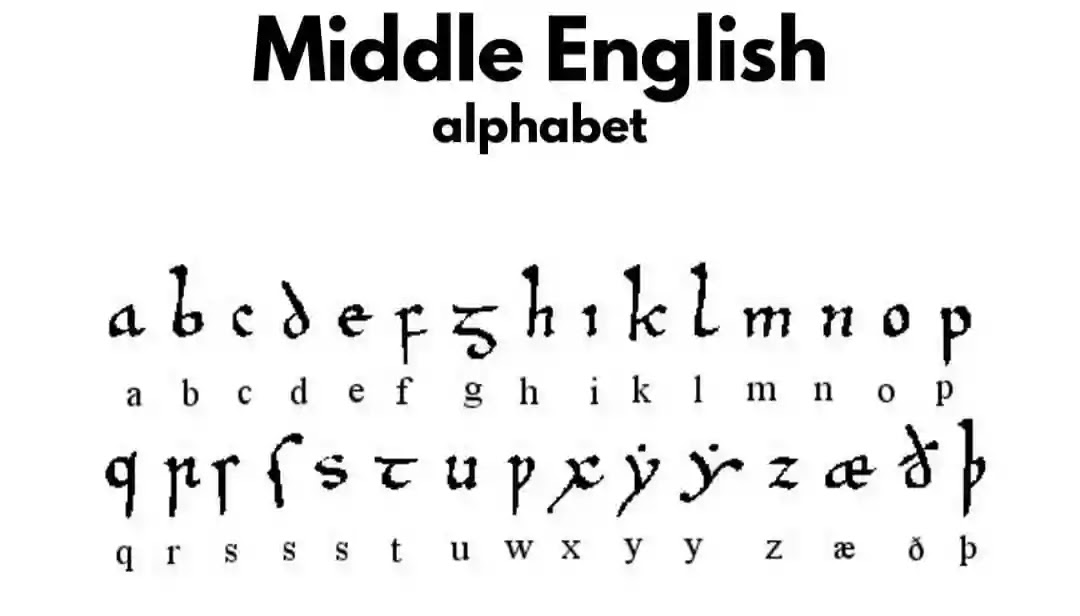

A good part of the reason for many of the vagaries and inconsistencies of English spelling has been attributed to the fact that words were fixed on the printed page before any orthographic consensus had emerged among teachers and writers. Printing also directly gave rise to another strange quirk: the word the had been written for centuries as þe, using the thorn character of Old English, but, as no runic characters were available on the European printing presses, the letter “y” was used instead (being closest to the handwritten thorn character of the period), resulting in the word ye, which should therefore technically still be pronounced as “the”. It is only since the archaic spelling was revived for store signs (e.g. Ye Olde Pubbe) that the “modern” pronunciation of ye has been used.

As the Early Modern period progressed, there was an increased use of double vowels (e.g. soon) or a silent final “e” (e.g. name) to mark long vowels, and doubled consonants to mark a preceding short vowel (e.g. sitting), although there was much less consensus about consonants at the end of words (e.g. bed, glad, well, glasse, etc). The letters “u” and “v”, which had been more or less interchangeable in Middle English, gradually became established as a vowel and a consonant respectively, as did “i” and “j”. Also during the 16th Century, the virgule (an oblique stroke /), which had been a very common mark of punctuation in Middle English, was largely replaced by the comma; the period or full-stop was restricted to the end of sentences; semi-colons began to be used in additon to colons (although the rules for their use were still unclear); quotation marks were used to mark direct speech; and capital letters were used at the start of sentences and for proper names and important nouns. The grammarian John Hart was particularly influential in these punctuation reforms.

Standardization was well under way by around 1650, but it was a slow and halting process and names in particular were often rendered in a variety of ways. For example, more than 80 different spellings of Shakespeare’s name have been recorded, and he himself spelled it differently in each of his six known signatures, including two different versions in his own will!

The Bible

Two particularly influential milestones in English literature were published in the 16th and early 17th Century. In 1549, the “Book of Common Prayer” (a translation of the Church liturgy in English, substantially revised in 1662) was introduced into English churches, followed in 1611 by the Authorized, or King James, Version of “The Bible”, the culmination of more than two centuries of efforts to produce a Bible in the native language of the people of England.

As we saw in the previous section, John Wycliffe had made the first English translation of “The Bible” as early as 1384, and illicit handwritten copies had been circulating ever since. But, in 1526, William Tyndale printed his New Testament, which he had translated directly from the original Greek and Hebrew. Tyndale printed his “Bible” in secrecy in Germany, and smuggled them into his homeland, for which he was hounded down, found guilty of heresy and executed in 1536. By the time of his death he had only completed part of the Old Testament, but others carried on his labours.

Tyndale’s “Bible” was much clearer and more poetic than Wycliffe’s early version. In addition to completely new English words like fisherman, landlady, scapegoat, taskmaster, viper, sea-shore, zealous, beautiful, clear-eyed, broken-hearted and many others, it includes many of the well-known phrases later used in the King James Version, such as let there be light, my brother’s keeper, the powers that be, fight the good fight, the apple of mine eye, flowing with milk and honey, the fat of the land, am I my brother’s keeper?, sign of the times, ye of little faith, eat drink and be merry, salt of the earth, a man after his own heart, sick unto death, the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak, a stranger in a strange land, let my people go, a law unto themselves, etc.

Ironically, a scant few years after Tyndale’s execution, Henry VIII’s split with Roman Catholicism completely changed official attitudes to an English “Bible”, and by 1539 the idea was being wholeheartedly encouraged, and several new English language Bibles were published (including the “Coverdale Bible”, the “Matthew Bible”, the “Great Bible”, the “Geneva Bible”, the “Bishops Bible”, etc).

The “King James Bible” was compiled by a committee of 54 scholars and clerics, and published in 1611, in an attempt to standardize the plethora of new Bibles that had sprung up over the preceding 70 years. It appears to be deliberately conservative, even backward-looking, both in its vocabulary and its grammar, and presents many forms which had already largely fallen out of use, or were at least in the process of dying out (e.g. digged for dug, gat and gotten for got, bare for bore, spake for spoke, clave for cleft, holpen for helped, wist for knew, etc), and several archaic forms such as brethren, kine and twain. The “-eth” ending is used throughout for third person singular verbs, even though “-es” was becoming much more common by the early 17th Century, and ye is used for the second person plural pronoun, rather than the more common you.

The comparison below of the famous Beatitudes from Chapter 5 of the Gospel According to St. Matthew (in the Wycliffe, Tyndale and Authorized versions respectively) gives an idea of the way the language developed over the period:

| Wycliffe 1. And Jhesus, seynge the puple, wente vp in to an hil; and whanne he was set, hise disciplis camen to hym. 2. And he openyde his mouth, and tauyte hem, and seide, 3. Blessed ben pore men in spirit, for the kyngdom of heuenes is herne. 4. Blessid ben mylde men, for thei schulen welde the erthe. 5. Blessid ben thei that mornen, for thei schulen be coumfortid. 6. Blessid ben thei that hungren and thristen riytwisnesse, for thei schulen be fulfillid. 7. Blessid ben merciful men, for thei schulen gete merci. 8. Blessid ben thei that ben of clene herte, for thei schulen se God. 9. Blessid ben pesible men, for thei schulen be clepid Goddis children. 10. Blessid ben thei that suffren persecusioun for riytfulnesse, for the kingdam of heuenes is herne. | Tyndale 1. When he sawe the people, he went vp into a mountayne, and when he was set, his disciples came to hym, 2. And he opened hys mouthe, and taught them sayinge: 3. Blessed are the povre in sprete: for theirs is the kyngdome of heven. 4. Blessed are they that morne: for they shalbe comforted. 5. Blessed are the meke: for they shall inheret the erth. 6. Blessed are they which honger and thurst for rightewesnes: for they shalbe filled. 7. Blessed are the mercifull: for they shall obteyne mercy. 8. Blessed are the pure in herte: for they shall se God. 9. Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shalbe called the chyldren of God. 10. Blessed are they which suffre persecucion for rightwesnes sake: for theirs ys the kyngdome of heuen. | King James 1. And seeing the multitudes, he went vp into a mountaine: and when he was set, his disciples came vnto him. 2. And he opened his mouth, and taught them, saying: 3. Blessed are the poore in spirit: for theirs is the kingdome of heauen. 4. Blessed are they that mourne: for they shall be comforted. 5. Blessed are the meeke: for they shall inherit the earth. 6. Blessed are they which doe hunger and thirst after righteousnesse: for they shall be filled. 7. Blessed are the mercifull: for they shall obtaine mercie. 8. Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God. 9. Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall bee called the children of God. 10. Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousnesse sake: for theirs is the kingdome of heauen. |

Excerpt from the Gospel According to St. Matthew Ch. 26 (Douay version, 1582) (73 sec) (from Palgrave Macmillan).

Although the majority of the King James Version was quite clearly based on Tyndale’s (up to 80% of the New Testament and much of the Old Testament), it is often considered a masterpiece of the English language, and many phrases from it have become well-used in every day speech. It is still considered by many to be the definitive English version of “The Bible”, and its iconic opening lines “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth” are well known, as are many of its phrases (in addition to those borrowed from Tyndale), including how are the mighty fallen, the root of the matter, to every thing there is a season, bent their swords into ploughshares, set your house in order, be horribly afraid, get thee behind me, turned the world upside down, a thorn in the flesh, etc. Much of its real power, though, was in exposing the written language to many more of the common people.

Dictionaries and Grammars

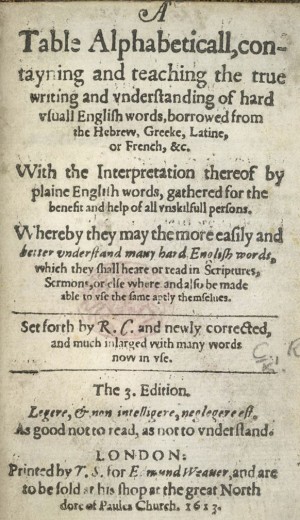

The first English dictionary, “A Table Alphabeticall”, was published by English schoolteacher Robert Cawdrey in 1604 (8 years before the first Italian dictionary, and 35 years before the first French dictionary, although admittedly some 800 years after the first Arabic dictionary and nearly 1,000 after the first Sanskrit dictionary). Cawdrey’s little book contained 2,543 of what he called “hard words”, especially those borrowed from Hebrew, Greek, Latin and French, although it was not actually a very reliable resource (even the word words was spelled in two different ways on the title page alone, as wordes and words).

Several other dictionaries, as well as grammar, pronunciation and spelling guides, followed during the 17th and 18th Century. The first attempt to list ALL the words in the English language was “An Universall Etymological English Dictionary”, compiled by Nathaniel Bailey in 1721 (the 1736 edition contained about 60,000 entries).

But the first dictionary considered anything like reliable was Samuel Johnson’s “Dictionary of the English Language”, published in 1755, over 150 years after Cawdrey’s. An impressive academic achievement in its own right, Johnson’s 43,000 word dictionary remained the pre-eminent English dictionary until the much more comprehensive “Oxford English Dictionary” 150 more years later, although it was actually riddled with inconsistencies in both spelling and definitions. Johnson’s dictionary included many flagrant examples of inkhorn terms which have not survived, including digladation, cubiculary, incompossibility, clancular, denominable, opiniatry, ariolation, assation, ataraxy, deuteroscopy, disubitary, esurine, estuation, indignate and others. Johnson also deliberately omitted from his dictionary several words he disliked or considered vulgar (including bang, budge, fuss, gambler, shabby and touchy), but these useful words have clearly survived intact regardless of his opinions. Several of his definitions appear deliberately jokey or politically motivated.

Since the 16th Century, there had been calls for the regulation and reform of what was increasingly seen as an unwieldy English language, including John Cheke’s 1569 proposal for the removal of all silent letters, and William Bullokar’s 1580 recommendation of a new 37-letter alphabet (including 8 vowels, 4 “half-vowels” and 25 consonants) in order to aid and simplify spelling. There were even attempts (similarly unsuccessful) to ban certain words or phrases that were considered in some way undesirable, words such as fib, banter, bigot, fop, flippant, flimsy, workmanship, selfsame, despoil, nowadays, furthermore and wherewithal, and phrases such as subject matter, drive a bargain, handle a subject and bolster an argument.

But, by the early 18th Century, many more scholars had come to believe that the English language was chaotic and in desperate need of some firm rules. Jonathan Swift, in his “Proposal for Correcting, Improving and Ascertaining the English Tongue” of 1712, decried the “degeneration” of English and sought to “purify” it and fix it forever in unchanging form, calling for the establishment of an Academy of the English Language similar to the Académie Française. He was supported in this by other important writers like John Dryden and Daniel Defoe, but such an institution was never actually realized. (Interestingly, the only country ever to set up an Academy for the English language was South Africa, in 1961).

In the wake of Johnson’s “Dictionary”, a plethora (one could even say a surfeit) of other dictionaries appeared, peaking in the period between 1840 and 1860, as well as many specialized dictionaries and glossaries. Thomas Sheridan attempted to tap into the zeitgeist, and looked to regulate English pronunciation as well as its vocabulary and spelling. His book “British Education”, published in 1756, and unashamedly aimed at cultured British society, particularly cultured Scottish society, purported to set the correct pronunciation of the English language, and it was both influential and popular. His son, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, later gave us the unforgettable language excesses of Mrs. Malaprop.

In addition to dictionaries, many English grammars started to appear in the 18th Century, the best-known and most influential of which were Robert Lowth’s “A Short Introduction to English Grammar” (1762) and Lindley Murray’s “English Grammar” (1794). In fact, some 200 works on grammar and rhetoric were published between 1750 and 1800, and no less than 800 during the 19th Century. Most of these works, Lowth’s in particular, were extremely prescriptive, stating in no uncertain terms the “correct” way of using English. Lowth was the main source of such “correct” grammar rules as a double negative always yields a positive, never end a sentence with a preposition and never split an infinitive. A refreshing exception to such prescriptivism was the “Rudiments of English Grammar” by the scientist and polymath Joseph Priestley, which was unusual in expressing the view that grammar is defined by common usage and not prescribed by self-styled grammarians.

The first English newspaper was the “Courante” or “Weekly News” (actually published in Amsterdam, due to the strict printing controls in force in England at that time) arrived in 1622, and the first professional newspaper of public record was the “London Gazette”, which began publishing in 1665. The first daily, “The Daily Courant”, followed in 1702, and “The Times” of London published its first edition in 1790, around the same time as the influential periodicals “The Tatler” and “The Spectator”, which between them did much to establish the style of English in this period.

Golden Age of English Literature

All languages tend to go through phases of intense generative activity, during which many new words are added to the language. One such peak for the English language was the Early Modern period of the 16th to 18th Century, a period sometimes referred to as the Golden Age of English Literature (other peaks include the Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and early 19th Century, and the computer and digital age of the late 20th Century, which is still continuing today). Between 1500 and 1650, an estimated 10,000-12,000 new words were coined, about half of which are still in use today.

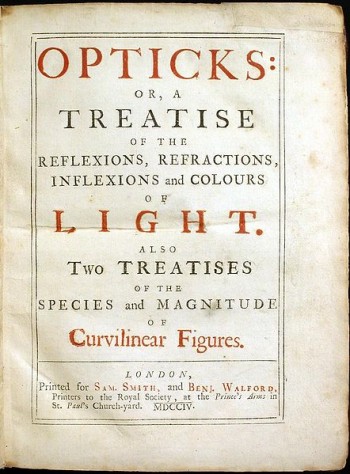

Up until the 17th Century, English was rarely used for scholarly or scientific works, as it was not considered to possess the precision or the gravitas of Latin or French. Thomas More, Isaac Newton, William Harvey and many other English scholars all wrote their works in Latin and, even in the 18th Century, Edward Gibbon wrote his major works in French, and only then translated them into English. Sir Francis Bacon, however, hedged his bets and wrote many of his works in both Latin and English and, taking his inspiration mainly from Greek, coined several scientific words such as thermometer, pneumonia, skeleton and encyclopaedia. In 1704, Newton, having written in Latin until that time, chose to write his “Opticks” in English, introducing in the process such words as lens, refraction, etc. Over time, the rise of nationalism led to the increased use of the native spoken language rather than Latin, even as the medium of intellectual communication.

Thomas Wyatt’s experimentation with different poetical forms during the early 16th Century, and particularly his introduction of the sonnet from Europe, ensured that poetry would became the proving ground for several generations of English writers during a golden age of English literature, and Edmund Spenser, William Shakespeare, John Donne, John Milton, John Dryden, Andrew Marvell, Alexander Pope and many other rose to the challenge. Important English playwrights of the Elizabethan era include Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, John Webster and of course Shakespeare.

The English scholar and classicist Sir Thomas Elyot went out of his way to find new words, and gave us words like animate, describe, dedicate, esteem, maturity, exhaust and modesty in the early 16th Century. His near contemporary Sir Thomas More contributed absurdity, active, communicate, education, utopia, acceptance, exact, explain, exaggerate and others, largely from Latin roots. Milton was responsible for an estimated 630 word coinages, including lovelorn, fragrance and pandemonium. Ben Jonson, a contemporary of Shakespeare, is also credited with the introduction of many common words, including damp, defunct, strenuous, clumsy and others; John Donne gave us self-preservation, valediction and others; and to Sir Philip Sydney are attributed bugbear, miniature, eye-pleasing, dumb-stricken, far-fetched and conversation in its modern meaning.

It was really only in the 17th Century that dialects (or at least divergence from the fashionable Standard English of Middlesex and Surrey) began to be considered uncouth and an indication of inferior class. However, such dialects provided good comic material for the burgeoning theatre industry (a well-known example being the “rude mechanicals” of Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”) and, paradoxically, many dialect words were introduced into general usage in that way. The word class itself only acquired its modern sociological meaning in the early 18th Century, but by the end of the century it had become all-pervasive, to the extent that the mere sound of a Cockney accent was enough to brand the speaker as a vagabond, thief or criminal (although in the 19th Century, Charles Dickens was to produce great literature and sly humour out of just such preconceptions, explicitly using speech, vocabulary and accent for commic effect).

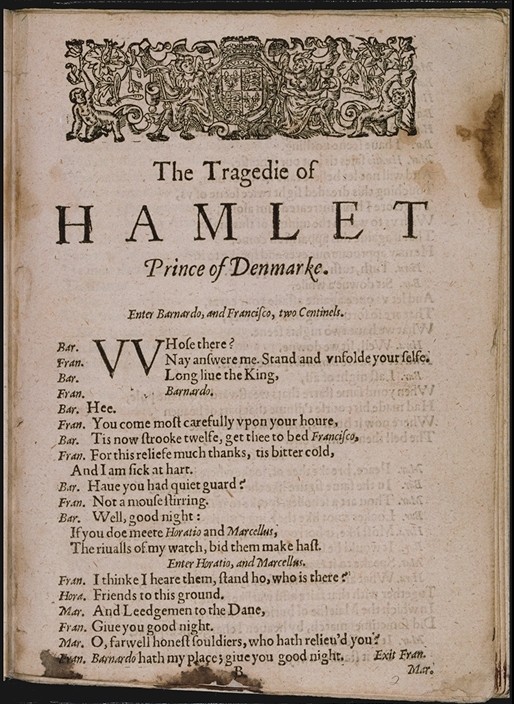

William Shakespeare

Whatever the merits of the other contributions to this golden age, though, it is clear that one man, William Shakespeare, single-handedly changed the English language to a significant extent in the late 16th and early 17th Century. Shakespeare took advantage of the relative freedom and flexibility and the protean nature of English at the time, and played free and easy with the already liberal grammatical rules, for example in his use nouns as verbs, adverbs, adjectives and substantives – an early instance of the “verbification” of nouns which modern language purists often decry – in phrases such as “he pageants us”, “it out-herods Herod”, dog them at the heels, the good Brutus ghosted, “Lord Angelo dukes it well”, “uncle me no uncle”, etc.

He had a vast vocabulary (34,000 words by some counts) and he personally coined an estimated 2,000 neologisms or new words in his many works, including, but by no means limited to, bare-faced, critical, leapfrog, monumental, castigate, majestic, obscene, frugal, aerial, gnarled, homicide, brittle, radiance, dwindle, puking, countless, submerged, vast, lack-lustre, bump, cranny, fitful, premeditated, assassination, courtship, eyeballs, ill-tuned, hot-blooded, laughable, dislocate, accommodation, eventful, pell-mell, aggravate, excellent, fretful, fragrant, gust, hint, hurry, lonely, summit, pedant, gloomy, and hundreds of other terms still commonly used today. By some counts, almost one in ten of the words used by Shakespeare were his own invention, a truly remarkable achievement (it is the equivalent of a new word here and then, after just a few short phrases, another other new word here). However, not all of these were necessarily personally invented by Shakespeare himself: they merely appear for the first time in his published works, and he was more than happy to make use of other people’s neologisms and local dialect words, and to mine the latest fashions and fads for new ideas.

He also introduced countless phrases in common use today, such as one fell swoop, vanish into thin air, brave new world, in my mind’s eye, laughing stock, love is blind, star-crossed lovers, as luck would have it, fast and loose, once more into the breach, sea change, there’s the rub, to the manner born, a foregone conclusion, beggars all description, it’s Greek to me, a tower of strength, make a virtue of necessity, brevity is the soul of wit, with bated breath, more in sorrow than in anger, truth will out, cold comfort, cruel only to be kind, fool’s paradise and flesh and blood, among many others.

By the time of Shakespeare, word order had become more fixed in a subject-verb-object pattern, and English had developed a complex auxiliary verb system, although to be was still commonly used as the auxiliary rather than the more modern to have (e.g. I am come rather than I have come). Do was sometimes used as an auxiliary verb and sometimes not (e.g. say you so? or do you say so?). Past tenses were likewise still in a state of flux, and it was still acceptable to use clomb as well as climbed, clew as well as clawed, shove as well as shaved, digged as well as dug, etc. Plural noun endings had shrunk from the six of Old English to just two, “-s” and “-en”, and again Shakespeare sometimes used one and sometimes the other. The old verb ending “-en” had in general been gradually replaced by “-eth” (e.g. loveth, doth, hath, etc), although this was itself in the process of being replaced by the northern English verb ending “-es”, and Shakespeare used both (e.g. loves and loveth, but not the old loven). Even over the period of Shakespeare’s output there was a noticeable change, with “-eth” endings outnumbering “-es” by over 3 to 1 during the early period from 1591-1599, and “-es” outnumbering “-eth” by over 6 to 1 during 1600-1613.

A comparison of a passage from “King Lear” in the 1623 First Folio with the same passage from a more familiar modern edition below gives some idea of some of the changes that were still underway in Shakespeare’s time:

Sir, I loue you more than words can weild ye matter, Deerer than eye-sight, space, and libertie, Beyond what can be valewed, rich or rare, No lesse then life, with grace, health, beauty, honor: As much as Childe ere lou’d, or Father found. A loue that makes breath poore, and speech vnable, Beyond all manner of so much I loue you. | Sir, I love you more than word can wield the matter, Dearer than eyesight, space, and liberty, Beyond what can be valued, rich or rare, No less than life, with grace, health, beauty, honour, As much as childe e’er loved, or father found. A love that makes breath poor and speech unable, Beyond all manner of ‘so much’ I love you. |

Other than the spellings of words such as weild, libertie, valewed and honor, the most obvious differences from modern-day spellings are the continued transposition of of “u” and “v” in loue and vnable, and the trailing silent “e” in lesse, Childe and poore, both hold-overs from Middle English and both in the process of transition at this time. However, it should be remembered that, just as with Chaucer, the Shakespeare folios we have today were compiled by followers such as John Hemming, Henry Condell and Richard Field, all of whom were not above making the odd change or “improvement” to the text, and so we can never be sure exactly what Shakespeare himself actually wrote.

Prologue from Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” in original dialect (45 sec).

Thee, thou and thy (signifying familiarity or social inferiority, as in most European languages today) were still very prevalent in Shakespeare’s time, and Shakespeare himself made good use of the subtle social implications of using thou rather than thou. Thee and thou had disapeared almost completely from standard usage by the middle of the 17th Century, paradoxically making English one of the least socially conscious of languages. The commonplace letter “e” found at the end of many medieval English words was also beginning its long decline by this time, although it was retained in many words to indicate the lengthening of the preceding vowel (e.g. name pronounced as “naim”, not as the Old English “nam-a”). The effects of the Great Vowel Shift were underway, but by no means complete, by the time of Shakespeare, as can be seen in some of his rhyme schemes (e.g. tea and sea rhymed with say, die rhymed with memory, etc).

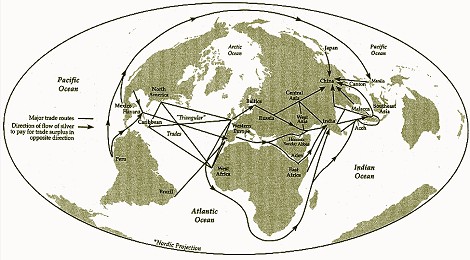

International Trade

While all these important developments were underway, British naval superiority was also growing. In the 16th and 17th centuries, international trade expanded immensely, and loanwords were absorbed from the languages of many other countries throughout the world, including those of other trading and imperial nations such as Spain, Portugal and the Netherlands. Among these were:

- French (e.g. bizarre, ballet, sachet, crew, progress, chocolate, salon, duel, brigade, infantry, comrade, volunteer, detail, passport, explorer, ticket, machine, cuisine, prestige, garage, shock, moustache, vogue);

- Italian (e.g. carnival, fiasco, arsenal, casino, miniature, design, bankrupt, grotto, studio, umbrella, rocket, ballot, balcony, macaroni, piano, opera, violin);

- Spanish (e.g. armada, bravado, cork, barricade, cannibal);

- Portuguese (e.g. breeze, tank, fetish, marmalade, molasses);

- German (e.g. kindergarten, noodle, bum, dumb, dollar, muffin, hex, wanderlust, gimmick, waltz, seminar, ouch!);

- Dutch/Flemish ( e.g. bale, spool, stripe, holster, skipper, dam, booze, fucking, crap, bugger, hunk, poll, scrap, curl, scum, knapsack, sketch, landscape, easel, smuggle, caboose, yacht, cruise, dock, buoy, keelhaul, reef, bluff, freight, leak, snoop, spook, sleigh, brick, pump, boss, lottery);

- Basque (e.g. bizarre, anchovy);

- Norwegian (e.g. maelstrom, iceberg, ski, slalom, troll);

- Icelandic (e.g. mumps, saga, geyser);

- Finnish (e.g. sauna);

- Persian (e.g. shawl, lemon, caravan, bazaar, tambourine);

- Arabic (e.g. harem, jar, magazine, algebra, algorithm, almanac, alchemy, zenith, admiral, sherbet, saffron, coffee, alcohol, mattress, syrup, hazard, lute);

- Turkish (e.g. coffee, yoghurt, caviar, horde, chess, kiosk, tulip, turban);

- Russian (e.g. sable, mammoth);

- Japanese (e.g. tycoon, geisha, karate, samurai);

- Malay (e.g. bamboo, amok, caddy, gong, ketchup);

- Chinese (e.g. tea, typhoon, kowtow).

- Polynesian (e.g. taboo, tatoo).